This comprehensive study guide delves into pivotal revolutions, examining their causes, key events, and lasting impacts. Resources include exam prep materials and detailed historical overviews, aiding in thorough comprehension.

Today is 12/31/2025 18:18:42 ()

The Enlightenment and its Influence

The Enlightenment, an 18th-century intellectual and philosophical movement, profoundly shaped revolutionary thought across the globe. Central to this era was an emphasis on reason, individualism, and skepticism towards traditional authority. Philosophers like John Locke articulated ideas of natural rights – life, liberty, and property – which became cornerstones of revolutionary ideologies.

These concepts directly challenged the divine right of kings and advocated for limited government, popular sovereignty, and the separation of powers. Montesquieu’s theories on the separation of powers, Rousseau’s social contract, and Voltaire’s advocacy for freedom of speech all fueled discontent with existing political structures.

The Enlightenment’s influence wasn’t limited to political thought. Scientific advancements, championed by figures like Isaac Newton, fostered a belief in progress and the power of human reason to solve societal problems. This intellectual climate created a fertile ground for questioning established norms and demanding reform, ultimately laying the ideological foundations for revolutions in America, France, and Latin America. The spread of Enlightenment ideas through salons, pamphlets, and books was crucial in mobilizing public opinion and inspiring revolutionary action.

Resources include exam prep materials and detailed historical overviews.

Causes of the American Revolution

The American Revolution stemmed from a complex interplay of political, economic, and ideological factors. Following the French and Indian War, Great Britain sought to exert greater control over its American colonies and recoup war debts. This led to a series of acts – the Stamp Act, Townshend Acts, and Tea Act – imposed without colonial representation in Parliament, sparking outrage under the cry of “No taxation without representation!”

Economic grievances played a significant role. British mercantilist policies restricted colonial trade, benefiting the mother country at the expense of colonial merchants and producers. The colonists desired economic freedom and the ability to trade with whomever they pleased.

Enlightenment ideals, as previously discussed, fueled a growing sense of colonial identity and a desire for self-governance. Colonial leaders, influenced by Locke and Montesquieu, argued for natural rights and the right to revolution against tyrannical rule. Increasing restrictions on westward expansion, coupled with British attempts to disarm colonial militias, further escalated tensions, ultimately leading to armed conflict at Lexington and Concord in 1775.

This comprehensive study guide delves into pivotal revolutions.

Key Events of the American Revolution

The American Revolution unfolded through a series of pivotal events, beginning with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, marking the start of armed conflict. The Second Continental Congress convened, forming the Continental Army and appointing George Washington as its commander.

A defining moment was the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, securing crucial French support for the American cause. Valley Forge (1777-1778) tested the Continental Army’s resilience during a harsh winter, but Washington’s leadership prevailed.

The British strategy shifted to the South, but ultimately failed at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, where a combined American and French force trapped Cornwallis’s army, effectively ending major combat operations.

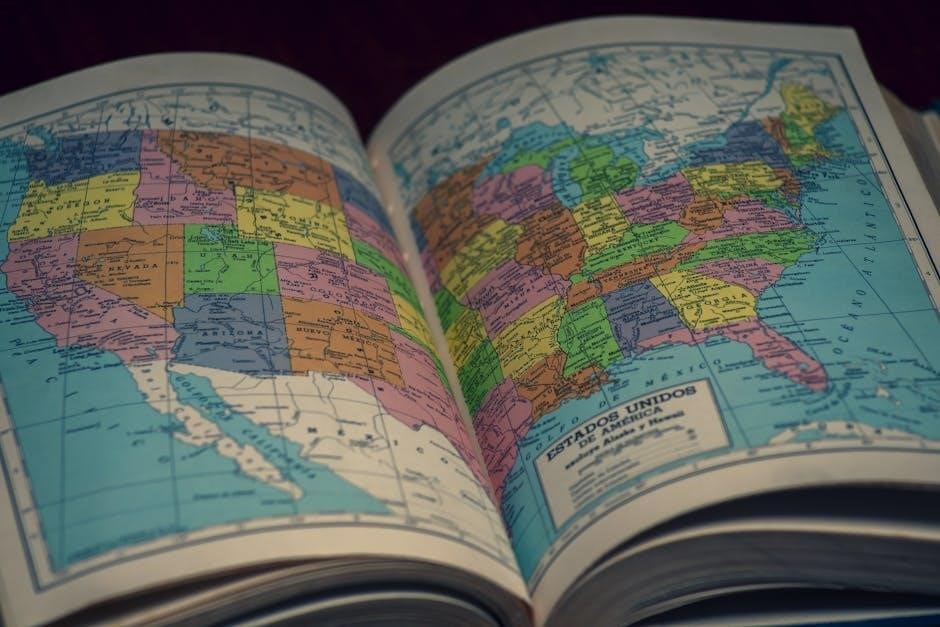

Significant battles included Bunker Hill, Trenton, and Princeton, each contributing to the evolving narrative of the war. These events, alongside diplomatic efforts, culminated in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, formally recognizing American independence and establishing the boundaries of the new nation. This period was crucial for shaping the future of the United States.

The Declaration of Independence

Adopted on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence stands as a cornerstone document in American history, articulating the principles of self-governance and individual rights. Primarily authored by Thomas Jefferson, it formally declared the thirteen American colonies independent from British rule.

The document’s core philosophy draws heavily from Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke, emphasizing natural rights – life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness – as inherent and inalienable. It outlines a list of grievances against King George III, justifying the colonies’ separation.

The Declaration is structured into five distinct parts: the preamble, a statement of beliefs, a list of grievances, a declaration of independence, and signatures. It asserts the right of the people to alter or abolish a government that becomes destructive of these ends.

Beyond its immediate political impact, the Declaration of Independence has served as an inspiration for independence movements and democratic ideals worldwide. It remains a powerful symbol of freedom and self-determination.

The Articles of Confederation

Ratified in 1781, the Articles of Confederation represented the first attempt to establish a unified government for the newly independent United States. It created a weak central government with limited powers, intentionally designed to avoid replicating the strong authority of the British monarchy.

The structure featured a unicameral legislature, the Confederation Congress, where each state held equal representation regardless of population; Crucially, the central government lacked the power to directly tax citizens or regulate interstate commerce, relying instead on voluntary contributions from the states.

Significant weaknesses plagued the Articles, including an inability to resolve disputes between states, enforce laws effectively, or raise a national army. Shay’s Rebellion in 1786-1787 vividly demonstrated the government’s impotence in suppressing domestic unrest.

Recognizing these fundamental flaws, leaders convened the Constitutional Convention in 1787 to revise the Articles. However, the outcome was a complete overhaul, leading to the drafting and eventual ratification of the United States Constitution, effectively replacing the Articles of Confederation.

The U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights

Emerging from the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the U.S. Constitution established a federal system of government, dividing powers between a national government and state governments. It introduced a bicameral legislature – the House of Representatives and the Senate – designed to balance representation based on population and state equality.

A key feature was the separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, each with distinct responsibilities and a system of checks and balances to prevent any one branch from becoming too dominant. This framework aimed to safeguard against tyranny.

Recognizing concerns about individual liberties, the Bill of Rights – the first ten amendments to the Constitution – was ratified in 1791. These amendments guarantee fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, religion, the press, the right to bear arms, protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, and the right to due process of law.

The Constitution and Bill of Rights remain foundational documents, shaping American law and governance, and serving as models for constitutionalism worldwide. They continue to be interpreted and debated in contemporary society.

The French Revolution: Causes

The French Revolution, erupting in 1789, stemmed from a complex interplay of long-term social, economic, and political factors. French society was rigidly divided into three Estates: the clergy, nobility, and commoners (the Third Estate). The Third Estate bore the brunt of taxation while lacking political representation.

Economic hardship was rampant, fueled by extravagant royal spending, costly wars (like supporting the American Revolution), and poor harvests leading to food shortages and soaring prices. This created widespread discontent among the peasantry and urban working class.

Enlightenment ideas, emphasizing reason, individual rights, and popular sovereignty, profoundly influenced revolutionary thought. Philosophers like Rousseau and Montesquieu challenged the legitimacy of absolute monarchy and advocated for a more just and equitable society.

Political weakness of the monarchy under Louis XVI, coupled with his indecisiveness and resistance to reform, further exacerbated the crisis. The summoning of the Estates-General in 1789, intended to address the financial crisis, instead ignited the revolution as the Third Estate demanded greater political power.

Key Events of the French Revolution

The French Revolution unfolded through a series of dramatic events. The Storming of the Bastille in July 1789, a symbolic act of defiance against royal authority, marked the revolution’s beginning. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted in August 1789, proclaimed fundamental rights like liberty, equality, and fraternity.

The Women’s March on Versailles in October 1789 forced the royal family to relocate to Paris, placing them under greater public scrutiny. The abolition of feudalism and the nationalization of Church lands followed, dismantling the old order.

The Reign of Terror (1793-1794), a period of extreme violence led by Maximilien Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety, saw the execution of thousands deemed enemies of the revolution. The Thermidorian Reaction ended the Reign of Terror and led to the establishment of the Directory.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup d’état in 1799 brought an end to the revolutionary period, ushering in a new era of French history. These events fundamentally reshaped France and influenced political thought across Europe.

The Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror, spanning 1793-1794, was a dark and violent chapter of the French Revolution. Driven by radical Jacobins, particularly Maximilien Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety, it aimed to purge France of enemies of the Revolution and establish a “Republic of Virtue.”

The Law of Suspects broadened the definition of treason, leading to mass arrests and trials. Revolutionary Tribunals swiftly condemned individuals, often with little evidence, resulting in thousands of executions by guillotine. Estimates suggest around 17,000 were officially executed, and another 10,000 died in prison or without trial.

Political factions, like the Girondins, were targeted, and even former revolutionaries faced the guillotine. The Terror extended beyond Paris, with repression occurring in regions resisting central authority. Dechristianization policies were implemented, including the closure of churches and the promotion of a secular “Cult of Reason.”

Ultimately, the excesses of the Terror led to Robespierre’s own downfall and execution in July 1794, marking the end of this brutal period. It remains a controversial and cautionary tale of revolutionary zeal gone awry.

Exam prep materials and detailed historical overviews aid in comprehension.

Napoleon Bonaparte and His Rise to Power

Napoleon Bonaparte’s ascent from Corsican artillery officer to Emperor of France was remarkably swift. He capitalized on the instability following the French Revolution, demonstrating military brilliance during campaigns in Italy and Egypt. His victories boosted his popularity and provided opportunities for political maneuvering.

In 1799, Napoleon orchestrated a coup d’état, overthrowing the Directory and establishing the Consulate, with himself as First Consul. This marked the end of the revolutionary period and the beginning of Napoleonic rule. He consolidated power through a combination of military success, shrewd political tactics, and propaganda.

As First Consul, Napoleon implemented significant reforms, including the Napoleonic Code – a comprehensive legal system that influenced law across Europe. He centralized government, stabilized the economy, and fostered national pride. In 1804, he crowned himself Emperor, solidifying his autocratic control.

Napoleon’s rise was fueled by a desire for order and stability after years of revolution, coupled with his undeniable military genius and ambition. He presented himself as a savior of France, restoring its glory and expanding its influence.

Napoleonic Wars and Their Impact

The Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) were a series of major conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies against a fluctuating array of European powers. Driven by Napoleon’s ambition to dominate Europe, these wars reshaped the continent’s political landscape.

Early French victories at Austerlitz and Jena-Auerstedt established French hegemony, leading to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine. However, resistance grew, particularly in Spain and Portugal, initiating the Peninsular War – a draining conflict for France.

The disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812 marked a turning point. The harsh winter and Russian scorched-earth tactics decimated Napoleon’s Grande Armée. A renewed coalition of European powers defeated Napoleon at Leipzig in 1813, leading to his abdication and exile to Elba.

Napoleon’s brief return during the Hundred Days ended with his final defeat at Waterloo in 1815. The wars’ impact was profound: the Congress of Vienna redrew European borders, restoring a balance of power and ushering in a period of relative peace. Nationalism surged across Europe, and the seeds of future conflicts were sown.

Revolutions in Latin America: Causes

Several interconnected factors fueled the revolutions sweeping through Latin America in the early 19th century. Colonial grievances, rooted in centuries of Spanish and Portuguese rule, were paramount. The peninsulares (those born in Spain or Portugal) held most political power, excluding the criollos (American-born descendants of Europeans) from high office.

Economic restrictions imposed by the mother countries stifled colonial economies. Mercantilist policies limited trade, forcing colonies to sell raw materials cheaply and buy manufactured goods at inflated prices. Heavy taxation further burdened the population.

Enlightenment ideas, circulating among the educated criollo class, inspired calls for liberty, equality, and self-governance. The success of the American and French Revolutions provided a powerful example of colonial rebellion.

Napoleon’s invasion of Spain in 1808 created a power vacuum, weakening Spanish control over its colonies. Criollo elites seized the opportunity to demand greater autonomy, ultimately leading to independence movements across the region. Social hierarchies and racial tensions also played a significant role in shaping revolutionary dynamics.

Key Figures in Latin American Revolutions

Several charismatic leaders spearheaded the independence movements across Latin America. Simón Bolívar, known as “The Liberator,” played a crucial role in liberating Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. His military genius and political vision were instrumental in establishing independent republics.

José de San Martín, another key figure, led the fight for independence in Argentina, Chile, and Peru. He strategically coordinated his efforts with Bolívar, though differing views on the future political organization of the region led to a famous meeting in Guayaquil.

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Mexican priest, initiated the Mexican War of Independence with his “Grito de Dolores” in 1810. Though executed early in the conflict, his call to arms ignited a decade-long struggle.

Toussaint Louverture, though leading the Haitian Revolution (often considered separately), profoundly influenced Latin American independence movements. His successful slave revolt demonstrated the possibility of overthrowing colonial powers. These leaders, along with countless others, embodied the spirit of resistance and the pursuit of self-determination.

Independence Movements in Latin America

The early 19th century witnessed a wave of independence movements sweep across Latin America, fueled by Enlightenment ideals and discontent with Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule. Criollos – people of Spanish descent born in the Americas – often led these movements, seeking greater political and economic autonomy.

Venezuela’s independence, spearheaded by Simón Bolívar, began in 1811, marked by fierce battles and political maneuvering. Argentina declared independence in 1816, followed by Chile in 1818 after San Martín’s campaigns. Peru achieved independence in 1821, though Spanish loyalists continued resistance for several years.

Mexico’s path to independence was more protracted, beginning with Hidalgo’s revolt in 1810 and culminating in independence in 1821. Brazil’s independence, unique among Latin American nations, occurred relatively peacefully in 1822 with the declaration of independence by Dom Pedro I.

These movements were often characterized by internal divisions, regional rivalries, and prolonged warfare. Despite these challenges, they ultimately resulted in the creation of numerous independent nations, reshaping the political landscape of the Americas.

Comparing Revolutions: American, French, and Latin American

While distinct, the American, French, and Latin American Revolutions shared common threads. All were inspired by Enlightenment ideals – liberty, equality, and popular sovereignty – challenging existing power structures. However, their causes and outcomes differed significantly.

The American Revolution focused on colonial independence from British rule, driven by grievances over taxation and representation. The French Revolution was a more radical upheaval, aiming to dismantle the entire social and political order, leading to widespread violence. Latin American revolutions primarily sought independence from colonial powers, but were often complicated by social hierarchies and regional conflicts;

The American Revolution resulted in a relatively stable republic, while the French Revolution experienced cycles of radicalism and reaction. Latin American nations faced prolonged instability and political fragmentation after independence.

A key difference lay in social structures; the American Revolution didn’t drastically alter social hierarchies, whereas the French and Latin American revolutions aimed for more profound social change, though with varying degrees of success; Ultimately, each revolution shaped the modern world in unique ways.

Long-Term Effects of the Revolutions

The revolutions of the late 18th and early 19th centuries profoundly reshaped the global political landscape. The American Revolution inspired democratic movements worldwide, demonstrating that colonial independence was achievable. The French Revolution, despite its turmoil, spread ideals of nationalism and citizenship, influencing political thought across Europe.

In Latin America, independence movements led to the creation of new nations, though often plagued by political instability and economic challenges. These revolutions contributed to the decline of colonialism and the rise of nation-states. They also spurred reforms in areas like education and legal systems.

Furthermore, the revolutions fostered the growth of liberalism and republicanism, challenging traditional monarchies and aristocratic privileges. The concept of self-determination gained prominence, influencing future independence movements. However, the legacy of these revolutions is complex, with ongoing debates about their impact on social equality and political development.

Ultimately, these upheavals laid the foundation for many of the political and social structures we see today, shaping modern ideologies and international relations.